“The fool considers himself wise, yet a wise man is aware of being a fool.”

— William Shakespeare, As You Like It.

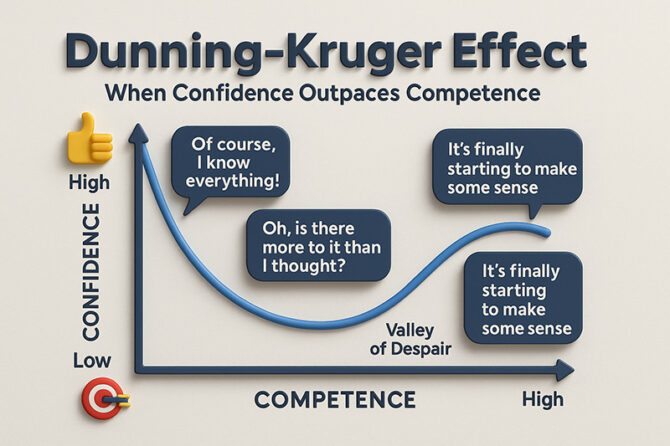

Centuries prior to current psychology, Shakespeare had already encapsulated what researchers David Dunning and Justin Kruger would codify much later, in 1999, as the Dunning–Kruger Effect. That intriguing psychological effect describes why individuals with little knowledge or skill tend to overestimate their talents, whereas genuine experts, who are conscious of much of what they don’t know, have a propensity for downgrading theirs. It is a contradiction of the human intellect — the less we know, the more sure we become of our belief, while the more than we know, the more humble and doubtful we become.

When Dunning and Kruger did the original study, they had participants rate their own performance on grammar, logic, and humour. Ironically, the least competent participants highly overrated, while the best participants tended to underestimate their own competence. The researchers concluded what many have concluded: incompetence steals from people the very knowledge of their own incompetence. That is, ignorance not just causes error, but also keeps the error hidden from our own knowledge.

At the onset of any learning experience, knowledge appears ridiculously easy. Excitement at learning new things makes us overconfident about how much we already know. This is commonly referred to as a “Mount Stupid” — a metaphorical peak of self-assured ignorance. As soon as we experience complexity, contradiction, our confidence promptly takes a dip — the “Valley of Despair.” With time, reflection, we gradually emerge on the “Slope of Enlightenment,” here competence gradually goes up, side by side with humility. Expertise is fashioned here, not hubris.

In this era of digital existence, the Dunning–Kruger Effect is everyday fodder. Social media is full of people boldly opining on medicine, economics, or politics after reading little or no information. The delusion of knowledge travels faster than actual knowledge. In medicine, for example, a newly graduated physician may overestimate their diagnostic capabilities after getting top marks on exams, while a grizzled clinician, tempered by years of uncertainty, is cautious and thoughtful. Swami Vivekananda said, “Education is the manifestation of the perfection already in man.” True education, however, also instils the awareness of imperfection — the modesty to be a student for life.

In the business world, this thought distortion manifests in utmost subtle yet decisive ways. A young professional, buoyed up due to initial success, might ignore the suggestions of experienced workers, supposing that the issue is less complex than it seems. Specialists with extensive knowledge, on the other hand, might refrain from contributing due to the nagging belief that they do not quite know what they know — a condition commonly referred to as impostor syndrome. And so, the Dunning–Kruger Effect and the impostor syndrome constitute two sides of the same mental spectrum: one out of ignorance, the other out of awareness.

Interestingly, the impact is not a complete nadir. Early over belief is a spur of impudence and incentive. It gives people courage to risk and embark on projects which otherwise would appear too scary for them. Innovators started being under the belief that what they sought was less difficult than it actually was — and their ignorance became the seed of invention. As Steve Jobs once exhorted, “Stay hungry, stay foolish.” A dash of preliminary foolishness tends to ignite the first step on the road towards wisdom.

Yet, it is a bad thing when left unbridled. That same fearlessness that stimulates activity can, at the same time, deafen people to lessons and criticism. Decisions, without proper knowledge, when made in areas such as medicine, tech, or politics, have serious, even deadly, consequences. In the COVID-19 era, for example, misinformation ran rampant when individuals without scientific education presented views with unwarranted surety. As wisely noted by Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, “Confidence and hard work are the best medicine to kill the disease called failure.” Confidence, without knowledge, can, however, prove a disease in itself — a perilous false sense of knowledge.

Ancient Indian philosophy insistently stressed humility as the essence of genuine learning. The Bhagavad Gita (4.34) instructs: “Approach those who have realized the truth. Inquire from them with humility and render service unto them.” This culture of humble inquiry stands in marked contrast to the arrogance of perceived knowledge. Likewise, the Upanishads talk about “Aham avidyaya ananditah” — “I rejoice in knowing that I do not know” — a deep realization that knowledge of ignorance is a sort of enlightenment per se. Chanakya, the brilliant rater, said the same thing in the Arthashastra: “He who knows one thing imagines he knows everything; he who knows everything imagines he knows nothing.” Self-knowledge of ignorance, paradoxically, is the ultimate form of wisdom.

To escape the Dunning–Kruger trap, self-knowledge and intellectual modesty are required. Soliciting honest criticism from mentors and fellow students deflates the bubble of exaggerated confidence. Accepting a lifetime of learning keeps pace with the realization that expertise is dynamic, not fixed, changing with each new discovery, each new insight. Learning from our mistakes — instead of concealing them — fortifies metacognition, thought about our own thought. This is beautifully encapsulated in the Zen ideology of Shoshin, or “beginner’s mind”: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind there are few.” The aim is to remain open, without being reduction-pleasured, knowledge held loosely, questions asked constantly.

The Dunning–Kruger Effect then finally reminds us that confidence and competence don’t develop on perpendicular lines. Confidence tends to come early, yet competence follows late, ripening only with experience, with a dash of humility, and through hard work. The path from ignorance to insight is neither straight nor easy; there are periods of doubting oneself, of rediscovery. And yet, when we cross the valley between the realm of illusion and the world of understanding, then, at the end, wisdom is not about knowing much, but about recognizing how little one does, in actuality, know.

As Socrates proclaimed over two millennia ago, “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.” The Dunning–Kruger Effect does not doom us to ignorance — it encourages us to humility. It instructs that the true expert is not the one who says they have all the questions answered, but the one who continues asking better questions.

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

My Values: Creating value for others.

Leave a reply

Leave a reply