In his book “Talking to Strangers,” Malcolm Gladwell refers to an appalling incident that shows how one of the oldest flaws of human behaviour—the inability to correctly assess strangers—remains unchanged to this day. In 1938, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain from Britain decided to personally meet Adolf Hitler at Munich to learn his real intentions. After lengthy talks, Chamberlain returned home “confident” that his new acquaintance intended to remain at peace and nothing but peace would come of it (Gladwell, 2019). History knows better than Gladwell wrote: World War II broke out just one year later.

Chamberlain’s miscalculation was not simply a failing of diplomacy—but one of those classic human errors that is best explained by how our brains are biologically wired to assess strangers. After all, few of us will ever have the sort of world-building role held by Chamberlain—but we all have to make these same kind of decisions every single day: at work, out in public spaces, or just on social media for example. And also crucially, modern behavioural psychology has shown conclusively that we are just very bad at judging strangers (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1992).

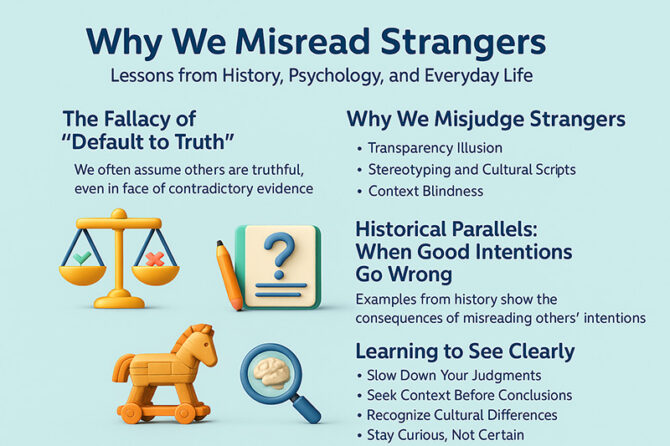

The Fallacy of “Default to Truth”

Gladwell points out another cognitive bias called “default to truth,” which was first coined by psychologist Timothy R. Levine, whose studies indicate that all humans have the tendency to trust others to tell the truth unless they have compelling reasons to believe otherwise (Levine, 2014). Chamberlain did want to believe Hitler. His emotional need for peace overshadowed the signs of aggression already apparent in Europe.

This is also what happens in real-life situations. At work, we tend to trust charismatic co-workers instead of introverted ones even though charisma is uncorrelated to trustworthiness. Scammers on social media succeed because we tend to take sincerity for granted instead of assuming deception. This is what Indian teacher and philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti wrote: “The ability to observe without evaluating is the highest form of intelligence.”

Why We Misjudge Strangers: The Behavioural Science Behind It

Modern social psychology provides various explanations:

1. Transparency Illusion

We argue that feelings inside should complement feelings shown externally. This is nothing but an illusion because many cultures tend to hide feelings of fear, anger, or uncertainty. Gladwell talks about trained professionals such as judges and intelligence officials who “don’t read” faces correctly very often (Gladwell, 2019).

2. Stereotyping and Cultural Scripts

Humans have to use cognitive shortcuts. These shortcuts are often culturally constructed or personally generated and tend to have very predictable biases. This theme is demonstrated very effectively through the story of Karna in the Indian epic “Mahabharata,” where Karna is readily rejected at the archery competition because of his apparent low status, to discover later his unparalleled skill and royal ancestry.

3. Context Blindness

But Stanford University psychologist Philip Zimbardo showed just how differently normal individuals act under specific role and environmental situations (Zimbarto, 2007). When making judgments of strangers incorrectly, we tend to disregard factors of pressures, fears, or rewards for their behaviour.

Historical Parallels: When Good Intentions Go Wrong

The infamous “handshake” between Chamberlain and Hitler is now universally recognized as a metaphor for mistaken judgment. But examples of mistaken judgment exist across cultures:

The Fable of the Snake and Farmer (Panchatantra)

A farmer gets hold of a frozen snake and takes care of it to bring it back to life. But after reviving it, it bites him too. The implication is obvious: we tend to project our goodness onto others and expect them to do the same to us too someday.

The Trojan Horse

The Greeks tricked the Trojans by presenting them with a wooden horse as ‘a gift of peace.’ The Trojans misunderstood the gesture behind it and suffered for it by losing their city state. This is one such incident from the past (Virgil’s Aeneid) which corroborates Chamberlain’s notion of good gestures being automatically replicated on the receiving side.

Misreading in Modern Life: A Behavioural Reflection

We tend to believe that misjudgements happen rarely. But they are integral to our daily routine:

Concerning hospital settings, patients may have their pain underestimated by health care professionals because they remain composed—the subject of studies on empathy among caregivers (Derksen et al., 2013).

In management or leadership positions, for instance, leaders may favour confident communicators over introverted team members for any particular task or activity.

In relationships, individuals often conflate politeness for care, argument for anger, or quiet for disapproval.

The renowned international speaker Wayne Dyer also said: “When you judge another person, you don’t define them—you define yourself.” What we interpret is much more indicative of our own thinking than what is standing right before us.

Learning to See Clearly: What History and Psychology Teach Us

Improving our knowledge and understanding of strangers is not easy but takes time and humility.

1. Slow Down Your Judgments

Fast interpretations may result from intuition, which is highly unreliable for unknown individuals.

As Mahatma Gandhi advised: “Action expresses priorities.” Consider behaviour over time rather than at first glance.

2. Seek Context Before Conclusions

Ask what forces may influence this person’s behaviour. Behaviour is never random but is always conditioned.

3. Cultural Differences Awareness

A thing may seem rude or arrogant or evasive because of its culture’s norms for communication. Cross-cultural psychology illustrates enormous differences regarding eye contact, tone of voice, gestures, or expressions of emotion (Matsumoto, 2006).

4. Remain Curious but Not Certain

In his advises to rulers, Lord Chanakya wrote, “Observe, inquire and trust only after”

Curiosity will help us to remain non-judgmental instead of becoming biased.

Last Words:

The tragic misunderstanding between Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler is more than just a warning for politicians to learn from—the dangerous game of reading others is one we all participate in every single day. We encounter strangers daily and attempt to read between their lines to determine just whom they are. Psychology, history, and philosophy all have one thing to tell us: humans are lousy at reading strangers but can improve our performance by slowing down and learning to read in humility.

“’The right way to talk to strangers is with caution and humility.’ This is how Gladwell brings home one of the most vital lessons ever written: treat strangers wisely and treat them kindly too.”– Malcolm Gladwell.

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

My Values: Creating value for others.

References

- Gladwell M. Talking to Strangers. Little, Brown and Company; 2019.

- Levine TR. Truth-Default Theory. Journal of Communication. 2014;64(6):993-1018.

- Ambady N, Rosenthal R. Thin slices of expressive behaviour. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111(2):256-274.

- Zimbardo P. The Lucifer Effect. Random House; 2007.

- Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):e76-e84.

- Matsumoto D. Culture, context, and behaviour. Journal of Personality. 2006;74(3):553-582.

Dear Dr. Prahlada N.B Sir,

The metaphor of handshake between Chamberlain and Hitler best illustrates how we misjudge minds of strangers! One should be pragmatic to read minds of people. It all depends on time, culture, behavior, conceptions, because face can never be the index of mind always.

Your astute observation resonates deeply, sir. The infamous handshake between Chamberlain and Hitler is a stark reminder of the dangers of misreading intentions. Like the proverbial still waters that run deep, the Führer's demeanor belied his true intentions, leading to catastrophic consequences.

Similarly, the tale of the Indian king, Vikramaditya, and the mysterious yogi, serves as a poignant reminder to look beyond facades. The yogi's calm demeanor hid his sinister intentions, much like the calm surface of a wolf-filled well.

In our own lives, we often encounter individuals who present themselves as 'angels' but harbour ulterior motives. Like the proverbial 'wolf in sheep's clothing,' they cloak their true intentions, making it imperative for us to be vigilant and discerning.

The Japanese art of 'Honne' and 'Tatemae' also comes to mind – the distinction between one's true intentions (Honne) and outward behavior (Tatemae). It's a delicate balance, indeed, to navigate the complexities of human nature.

Your expertise in understanding human behavior and psychology offer invaluable insights into this intricate web of human interactions.

ReplyPrahalad! I felt you wrote perfectly, I can’t imagine/think what could have been any better than what was said about judging others. I do have to face the same when I come across so many people in my institutions. 👌👏🏻👍

Reply