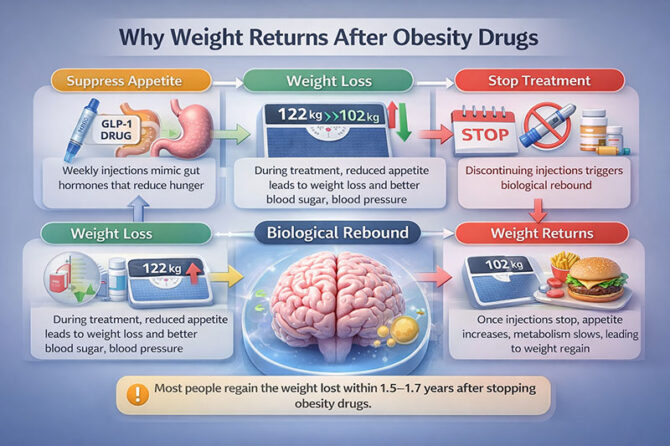

GLP-1 receptor agonist anti-obesity therapies like semaglutide and tirzepatide have transformed the way weight management is practiced today. For many patients, it is nothing short of a transformative experience, with appetites diminishing, portion sizes shrinking effortlessly, metabolism parameters optimizing, and double-digit percentage reductions in weight becoming feasible even in a matter of months. Yet, the truth that has come to be understood through the availability of real-world data is that maintaining weight lost through these medications is not feasible.

A large systematic review and meta-analysis, published in The BMJ, with data from more than 9,300 patients in 37 studies, followed the outcome after stopping weight loss medications. The results are consistent and alarming. On average, patients regained about 0.4 kg/month, reaching baseline weight in 1.5 to 1.7 years. This was even quicker for the newer GLP-1 medications, which result in greater weight reduction (typically 15 kg), with a weight regain rate close to 0.8 kg/month in some studies

Biology, Not Willpower, Explains the Rebound

This predictable rebound is not a lack of discipline. Obesity is now understood to be a biologically governed chronic condition, subject to complex neuro-hormonal feedback mechanisms that protect body weight. A loss of body weight triggers a neuro-hormonal response to protect against starvation. Hunger hormones increase, feelings of satiety decrease, and metabolic rate declines due to thermogenesis. Fat cells also become more metabolically efficient at storing calories. This occurs even when the weight loss is sustained.

GLP-1 drugs work around the system by inhibiting appetite, slowing the emptying of the stomach, and inhibiting reward-driven eating. However, these drugs do not treat the biological system by reprogramming it. When the drugs are stopped, the body’s defensive responses come into play, resulting in steady weight regain.

As endocrinologist Rudolph Leibel has famously said, “The body has multiple redundant systems to prevent weight loss and very few systems to prevent weight gain.” This observation is strongly borne out by the evidence.

Why Lifestyle Weight Loss is So Different

What is noteworthy here is that weight regain in behavioural interventions, such as diet and exercise programs, occurs at a slower rate (approximately 0.1 kg per month). While weight regain does happen, structured behavioural programs put their participants under compulsion to develop strategies to cope with their weight problems. This might help mitigate weight rebound in some measure.

The weight loss resulting from medications can often circumvent this process. The reduction in appetite eliminates the need for self-control. Patients are left with unrestrained biological drives when the pharmacologic aid is discontinued and the enhanced behavioural protection mechanisms have not been developed.

Implications for Clinical Practice and the Indian Health System

The implications here are very significant. The cost of these GLP-1 drugs can range into tens of thousands of rupees a month. This is a cost that is completely beyond the reach of the common man. If the long-term effect of these drugs is to be believed, which is to provide a beneficial effect on the metabolism and the cardiovascular system, then the short-term effect can be nothing but a cosmetic reduction of weight.

From a public health viewpoint, there are questions of equity, sustainability, and medicalization. As Mahatma Gandhi has reminded us, “It is health that is real wealth, and not pieces of gold and silver.” An over-reliance on costly pharmacology, without developing prevention and behaviour infrastructure, threatens to exacerbate health inequities.

On the international level, the lesson is part of a general paradigm of treatment for chronic diseases. In the words of physician/writer Atul Gawande, “Better medicine is not just about new technologies, but about better systems.” The treatment of obesity must also shift from short-term approaches to long-term systems of care.

The Larger Lesson

The key finding of this research is not that the weight comes back after discontinuing injections—it is because it comes back. Obesity is protected by robust biological mechanisms. The GLP-1 drugs expose the strength and weakness of contemporary medical practice. The future is not about medical treatments versus lifestyle change, but about combining these options with a realistic and ethical approach. But with these therapies entering mainstream practice, the question is no longer how quickly the pounds come off—but how openly the healthcare community is discussing with patients what happens when the treatment is completed.

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

My Values: Creating value for others.

References:

- Liu Y, Yang J, Zhang D, et al. Weight regain after discontinuation of anti-obesity pharmacotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2024;385:e078654. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-078654.

Leave a reply