The recently published Viewpoint in The Lancet Regional Health – Southeast Asia by Samajdar, Joshi, Misra, and Vikram is a timely and courageous contribution to diabetes science in South Asia. The authors deserve appreciation not only for their clinical scholarship but also for their public health foresight. Equally, the journal merits commendation for providing an open-access platform to critically examine diagnostic practices that are often accepted without sufficient regional scrutiny.

HbA1c has long been regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing and monitoring type 2 diabetes (T2D). Its practical advantages are undeniable: it does not require fasting, reflects average glycemia over two to three months, and is embedded in global guidelines. However, as the authors argue with clarity and evidence, the biological and epidemiological realities of India render sole reliance on HbA1c problematic.

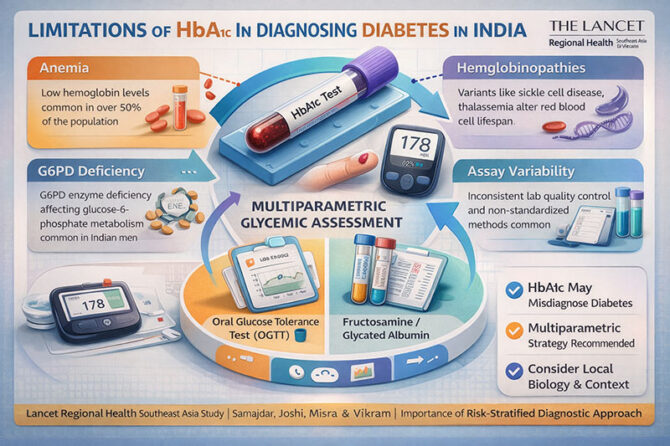

The article highlights a fundamental principle: HbA1c reflects glycation of hemoglobin—not glucose itself. Therefore, any condition that alters hemoglobin structure, red cell lifespan, or erythrocyte turnover can distort HbA1c values. In India, where iron deficiency anemia (IDA), hemoglobinopathies, and G6PD deficiency are prevalent, this is not a marginal caveat but a systemic limitation.

The magnitude of the issue is striking. A meta-analysis cited in the article reports anaemia prevalence exceeding 50% among Indian adults in several regions. Iron deficiency can either falsely elevate or suppress HbA1c depending on red cell dynamics. Meanwhile, haemoglobin variants such as sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia, and enzymatic disorders like G6PD deficiency—estimated at 7–8.5% nationally—shorten red cell lifespan and may produce falsely low HbA1c levels. The authors reference genomic evidence demonstrating that undiagnosed G6PD deficiency can delay diabetes diagnosis by over four years and increase microvascular complications. Such delays translate directly into preventable blindness, nephropathy, neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease.

Equally compelling is the discussion on diagnostic discordance. Indian studies reveal substantial mismatch between HbA1c and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) results. In one South Indian cohort, OGTT identified nearly twice as many cases of prediabetes as HbA1c, with minimal overlap. In other settings, HbA1c underestimated dysglycemia at international cut-offs, while in iron-deficient populations it overestimated prevalence. These findings underscore a core message: HbA1c may both under-diagnose and over-diagnose diabetes depending on biological context.

The authors also confront laboratory realities. Although HbA1c testing is widespread in India, standardization remains inconsistent. Not all assays are NGSP-certified, and even high-performance liquid chromatography may yield aberrant readings in the presence of haemoglobin variants. In a healthcare system where laboratory variability already challenges diagnostic consistency, over-reliance on a single imperfect biomarker compounds error.

Importantly, the article is not merely critical—it is constructive. The authors propose a multiparametric, risk-stratified framework for India. For diagnosis, OGTT remains the gold standard, especially in regions with high hematologic disorder prevalence. HbA1c may corroborate but should not replace glucose-based criteria. For monitoring, HbA1c should be interpreted alongside fasting and postprandial glucose values, and where feasible, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) metrics such as Time in Range (TIR) may provide superior insight.

Alternative markers—fructosamine, glycated albumin, and 1,5-anhydroglucitol—are discussed as adjuncts when HbA1c is unreliable. Though cost and availability limit their widespread adoption, they represent essential tools in complex cases. The inclusion of hematologic screening—complete blood count, red cell indices, iron studies, haemoglobin electrophoresis, and targeted G6PD testing—into diabetes workflows is a pragmatic and regionally appropriate recommendation.

From a policy standpoint, the implications are profound. National diabetes prevalence estimates based solely on HbA1c risk misrepresenting disease burden. This can distort resource allocation, screening strategies, and long-term health planning. A country with India’s heterogeneity cannot depend on uniform algorithms derived from Western populations. Diagnostic frameworks must reflect local biology, nutritional patterns, genetic variability, and laboratory infrastructure.

For clinicians, the advisory is clear: interpret HbA1c in context. When HbA1c and capillary glucose readings diverge, investigate rather than ignore. Elevated red cell distribution width, unexplained discordance, or presence of anaemia should prompt confirmatory testing. Clinical judgment must supersede numerical convenience.

For researchers, this Viewpoint signals an urgent need for India-specific diagnostic thresholds and longitudinal validation studies. Population-calibrated regression models for Hemoglobin Glycation Index (HGI), region-specific HbA1c cut-offs, and cost-effective screening tools must be developed.

In publishing this analysis, The Lancet Regional Health – Southeast Asia reinforces its role as a journal attentive to regional realities rather than global generalizations. The authors’ rigorous synthesis of biological, epidemiological, and laboratory evidence offers not just critique but a roadmap.

Ultimately, the article reminds us of a fundamental truth in medicine: biomarkers are instruments, not infallible arbiters. In India’s complex hematologic landscape, glycemic assessment must move beyond a single number. A nuanced, multiparametric approach—anchored in science and tailored to context—is not merely advisable; it is essential for equitable and accurate diabetes care.

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

My Values: Creating value for others.

Leave a reply

Leave a reply