The Aral Sea used to be the fourth largest inland body of water in the world, but now it is a symbol of bad environmental management. Kazakhstan’s fresh call for regional collaboration has once again brought international attention to this environmental disaster. The author and the publication platform should be thanked for bringing policy changes, diplomatic pronouncements, and restoration efforts on the ground to the world’s attention. If we want ecological issues to stay part of world conversation and not become footnotes in history, we need to keep writing about how to manage water across borders.

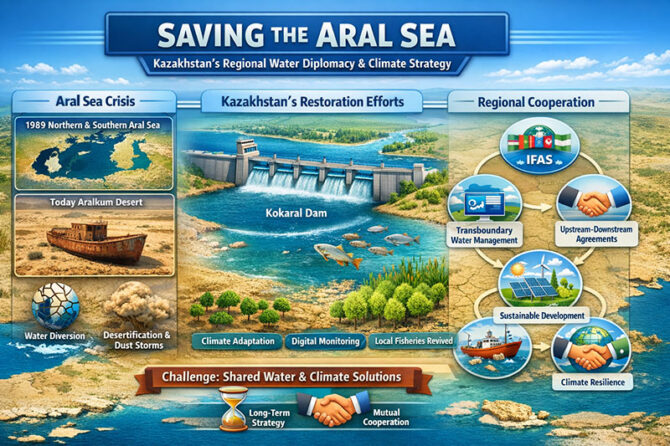

The Aral Sea, which located between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, started to decline in the 1960s when Soviet irrigation programs changed the flow of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers to make more cotton. The results were terrible. The sea had split into northern and southern basins by 1989. The eastern part of the Southern Aral Sea dried up completely in 2014, leaving behind the Aralkum Desert. This desert is now a source of deadly dust storms that spread salt and agricultural pollutants over Central Asia.

But the story isn’t just about loss that can’t be undone. Kazakhstan has been using targeted hydrological engineering to bring the Northern Aral Sea back to life. International funding helped build and strengthen the Kokaral Dam, which raised water levels in the northern basin. Salinity has gone down, native fish species have come back, and reports say that annual fish catches have gone up by more than ten times since the early 2000s. Fishing boats are back on the shore of the maritime town of Aralsk.

This partial recovery teaches us a crucial lesson: when politics and science-based action work together, ecological collapse can be slowed down and even partially stopped. But it also shows a bigger problem in the world of politics. Rivers don’t care about borders. The future of the Aral basin depends on how well the states above and downstream work together.

The International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS), which was set up in 1993, is the major way that water is coordinated in the region. Kazakhstan is currently in charge of the organization, and they are working to modernize it by using digital monitoring technologies and AI-supported water management across the entire basin. The idea of creating a single automated method for allocating water might make things more open, lower distrust, and make things work better.

Still, different national interests remain. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan put hydropower first and only let water out in the winter to make energy. Countries downstream, like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, need summer flows for farming. Marat Shibutov, a political expert, has said that downstream restoration won’t work without upstream cooperation. He points out that decisions about how to manage reservoirs have a direct impact on the effectiveness of Kazakhstan’s recovery initiatives.

The problem gets worse because of climate change. As temperatures rise, evaporation speeds up, and changes in precipitation patterns put river inflows at risk. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that Central Asia is one of the areas that is most likely to suffer from water stress as the world warms. “Water is the lifeblood of our world,” said former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. In the Aral basin, that lifeblood is getting harder to find.

Kazakhstan’s decision to include the restoration of the Aral Sea in its larger climate agenda is a smart move. Connecting basin recovery to global efforts to adapt and be resilient may open up climate funds and support from many countries. Planned regional climate summits give us a chance to make water diplomacy a long-term strategic goal instead of just a seasonal discussion.

From an Indian point of view, the Aral Sea is both a warning and a guide. India’s own disputes over rivers between states, such the Cauvery, and the depletion of groundwater in farming areas show how expanding agriculture and weak governance may upset the balance of nature. At the same time, the Ganga’s basin-level management efforts show that concerted strategy backed by data and institutional accountability may lead to real improvements. Sunita Narain, an environmentalist, has said, “We can’t solve today’s problems with yesterday’s thinking.” The Aral problem calls for exactly that change, from extraction to stewardship.

Kazakhstan’s planting of trees on the former seabed, covering hundreds of thousands of hectares to cut down on dust storms, is an example of adaptability in action. Under current conditions, the Southern Aral basin may not be able to be saved by hydrology, but stabilizing the environment and expanding the local economy can help people.

There are similarities between the shrinking of Lake Chad and arguments over the Colorado River around the world. Every case shows the same thing: shared water systems need shared management. Without diplomatic unity, engineering solutions alone won’t work.

People in Aralsk can see water coming back to their town. Fishing is back, and some families are coming back. But many in the area know how fragile this development is. For the Northern Aral Sea to get better, there needs to be long-term cross-border water releases, planning for climate resilience, and changes to institutions.

The narrative of the Aral Sea is no longer only about environmental disaster; it’s also about whether diplomacy in the region can turn ecological tragedy into cooperative rebirth. Kazakhstan’s request for more involvement is not just political talk; it is an acknowledgment that shared ecosystems can only survive if everyone takes responsibility.

The author and the publishing outlet that made this topic more visible again are doing an important service. In a time when climate change is happening faster and faster, accurate reporting keeps people interested and holds policymakers accountable. The Aral Sea may never be as big as it used to be, but its partial recovery shows that it is possible to recover if countries choose to work together instead of against each other and put long-term survival ahead of short-term gain.

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

My Values: Creating value for others.

Leave a reply

Leave a reply