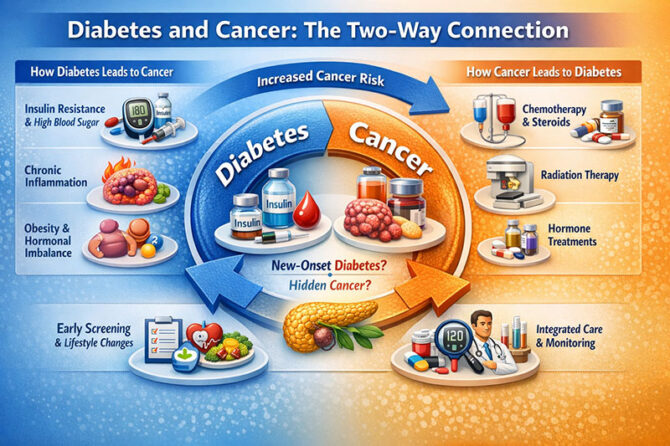

The relationship between diabetes and cancer is no longer viewed as coincidental or incidental. Over the past two decades, accumulating epidemiological data, mechanistic studies, and clinical observations have revealed a complex and bidirectional association between these two common chronic conditions. Diabetes appears to increase the risk of developing certain cancers, while cancer itself—and many of its treatments—can predispose individuals to new-onset diabetes. In an era marked by a global diabetes epidemic and steadily improving cancer survival, understanding this intersection has become a clinical and public health priority.

Indian endocrinologist Dr. V. Mohan has repeatedly emphasised that diabetes should be understood not as a single-organ disorder but as a systemic metabolic state that influences nearly every physiological pathway. Cancer biology, it now appears, is deeply affected by this metabolic milieu.

Large population-based studies and meta-analyses have consistently shown that people with type 2 diabetes have a higher incidence of specific malignancies, particularly pancreatic, liver, colorectal, breast, and endometrial cancers. This association is not uniform across all cancer types, suggesting that shared biological mechanisms play a selective role. Chronic hyperinsulinaemia and insulin resistance, hallmarks of type 2 diabetes, increase circulating insulin and insulin-like growth factor levels, both of which can stimulate cellular proliferation and inhibit apoptosis. Over time, this creates an environment favourable to malignant transformation. In parallel, diabetes is characterised by persistent low-grade inflammation, which promotes oxidative stress, angiogenesis, and genomic instability. Sustained hyperglycaemia further contributes by altering cellular metabolism and potentially fuelling tumour growth. A comprehensive review published in Seminars in Oncology in 2025 underscores that these links are biologically plausible and extend well beyond simple statistical correlation.

An important and often underappreciated dimension of this relationship is the observed gender disparity. Evidence from pooled international datasets indicates that women with diabetes experience a greater relative increase in overall cancer risk compared with men with diabetes. This excess risk is not confined to a single malignancy but spans multiple cancer types. The reasons are likely multifactorial, involving interactions between adiposity, insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and sex hormone dysregulation. Metabolic disturbances related to diabetes may persist longer or exert stronger effects on hormone-sensitive tissues in women. Professor Valerie Beral of Oxford University has noted that the interplay between metabolism, hormones, and cancer risk in women remains insufficiently recognised and underexplored, despite its clinical importance.

The bidirectional nature of the diabetes–cancer relationship becomes even more evident when examining cancer survivorship. Advances in oncology have led to a growing population of long-term cancer survivors, many of whom face delayed metabolic complications. A 2024 review in Annals of Medicine and Surgery highlighted how several commonly used cancer therapies disrupt glucose homeostasis. Chemotherapy and corticosteroids can induce significant hyperglycaemia, sometimes unmasking latent diabetes. Androgen deprivation therapy used in prostate cancer has been linked to worsening insulin resistance, while abdominal or pancreatic radiation can directly impair insulin secretion by damaging pancreatic tissue. Importantly, diabetes may develop months or even years after cancer treatment has ended, at a time when routine follow-up often prioritises recurrence surveillance rather than metabolic monitoring.

One of the most clinically significant advances in recent years has been the growing recognition of new-onset diabetes in older adults as a potential early warning sign of occult cancer, particularly pancreatic cancer. Unlike long-standing diabetes, which gradually increases cancer risk over time, sudden-onset diabetes after the age of 50—especially in individuals without obesity or a strong family history—may be a paraneoplastic phenomenon. Pancreatic tumours can interfere with insulin secretion well before they become radiologically apparent. Professor Suresh Chari, a leading authority in pancreatic cancer research, has described new-onset diabetes as one of the earliest clinical manifestations of pancreatic cancer rather than merely a consequence of it. This insight has spurred research into screening strategies that use new-onset diabetes as a trigger for targeted pancreatic evaluation, a development that holds promise for improving outcomes in a disease notorious for late diagnosis and poor survival.

The clinical implications of these findings are substantial. For individuals living with diabetes, awareness of elevated cancer risk reinforces the importance of regular, guideline-based cancer screening, particularly for colorectal, breast, and liver cancers. Maintaining good glycaemic control, engaging in regular physical activity, and managing body weight may not only reduce cardiovascular complications but also lower cancer risk. For cancer survivors, especially those exposed to steroids, radiation, or hormonal therapies, long-term monitoring of blood glucose levels is essential, even years after treatment completion. For clinicians, the diagnosis of diabetes in older adults should prompt careful clinical judgement rather than automatic categorisation as routine type 2 diabetes, particularly when the presentation is atypical.

Research at the interface of metabolic disease and oncology is now one of the most dynamic areas in medicine. Ongoing efforts aim to refine cancer therapies to minimise metabolic side effects, develop diabetes-based biomarkers for early cancer detection, and design survivorship programmes that integrate oncologic and endocrine care. As Sir David Weatherall once observed, medicine advances most rapidly at the borders between disciplines. The evolving understanding of the diabetes–cancer connection exemplifies this principle.

Living with diabetes does not mean that cancer is inevitable, nor does surviving cancer guarantee the development of diabetes. However, recognising the links between these conditions empowers patients and clinicians alike to pursue preventive strategies, engage in informed discussions, and adopt more personalised models of care. In medicine, the clues to one disease often lie hidden within another, and appreciating these connections is key to improving long-term health outcomes.

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

My Values: Creating value for others.

Leave a reply

Leave a reply