When nations approach a per capita income of around USD 3,000, healthcare policy becomes a defining economic choice rather than a peripheral welfare concern. This inflection point determines whether health is treated as a cost to be minimized or as foundational infrastructure that supports long-term growth. A revealing comparison emerges when India’s current health budget trajectory is viewed alongside China’s position in 2008, when both economies stood at roughly the same income level. China used that moment to initiate a decisive shift toward universal health coverage, while India continues to navigate similar challenges with far more limited fiscal commitment.

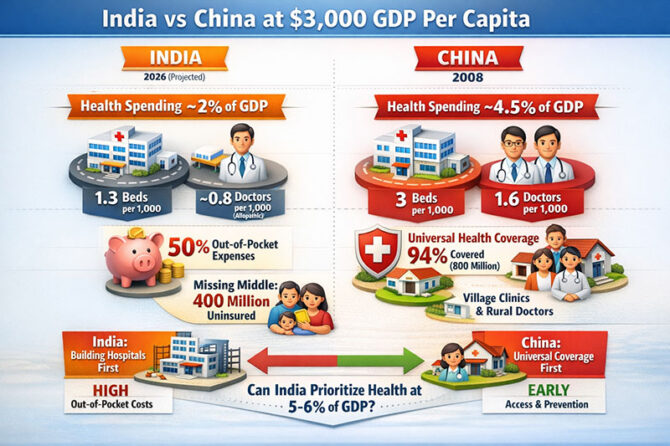

By the time China launched its major reforms, it had already invested heavily in hospitals and physician capacity. Hospital bed density had reached global norms, and doctor availability exceeded international recommendations. This prior investment allowed China to focus its next phase on financial protection and access. India, however, is still grappling with infrastructure shortages. Hospital bed availability remains around 1.3 per 1,000 population, far below international benchmarks. While headline figures suggest India has crossed the minimum physician threshold, this calculation includes AYUSH-certified practitioners. When only allopathic doctors are counted, physician density drops to approximately 0.8 per 1,000 population, revealing a much deeper workforce gap.

From a planning perspective, prioritizing hospital construction and tertiary care appears logical. Visible infrastructure reassures the public and addresses immediate, life-threatening conditions. Subsidized cancer drugs, trauma centers, and specialty hospitals undeniably save lives. On paper, building infrastructure first is not only reasonable but unavoidable in a system that has historically been underbuilt. Yet infrastructure alone does not explain why outcomes between India and China diverged so sharply after reaching similar income levels.

The critical difference lies in public spending. At comparable GDP per capita, China was spending roughly two and a half times more per person on healthcare than India does today. This disparity compounds over time. China allocated close to 4.5 percent of its GDP to health during its reform phase, while India continues to spend around two percent. Global evidence consistently shows that when public spending is low, households are forced to bear the burden directly. This is precisely what has happened in India, where out-of-pocket expenditure has hovered near 50 percent of total health spending for decades.

Although government programs such as Ayushman Bharat–PMJAY have meaningfully reduced catastrophic health expenditure for the poorest sections of society, a vast segment of the population remains uncovered. Nearly 400 million people, often described as the “missing middle,” earn too much to qualify for public insurance but too little to afford private coverage comfortably. For these households, illness represents not just a health crisis but an economic shock. As a result, families save defensively for medical emergencies rather than spending or investing. An Indian health economist once captured this reality succinctly by saying that health insecurity functions like a silent tax on consumption.

China addressed this problem by reversing the logic of healthcare delivery. Under the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme, the country prioritized universal financial protection and proximity of care. Public insurance coverage expanded rapidly to encompass nearly the entire population, including hundreds of millions of rural residents. Simultaneously, China revived village-level healthcare by reopening clinics and restoring the role of the village doctor. The goal was not simply to treat disease, but to ensure that illness was identified early, before it progressed silently into catastrophe. As former global health leaders have repeatedly emphasized, universal coverage is not a luxury; it stabilizes households and strengthens the economy.

India’s core challenge, however, is not a misplaced health strategy. Given fiscal constraints, choosing to strengthen hospitals and tertiary care is defensible. The real issue is that health has not yet been elevated to the level of a national economic priority. International experience suggests that meaningful universal health coverage requires public spending in the range of five to six percent of GDP. For India, this would mean tripling current allocations.

With adequate funding, the country could shift attention toward the top of the patient funnel, particularly in Tier-2, Tier-3, and rural regions where disease often goes undetected. Family doctors, early screening, and community-based care would reduce both clinical severity and long-term costs. A senior Chinese reformer once remarked that hospitals treat illness, but primary care prevents poverty—a lesson that remains deeply relevant for India today.

If public investment does not rise substantially, the private sector will inevitably step in. The missing middle represents one of the largest untapped health insurance markets globally. With full foreign direct investment now permitted, India is likely to see an influx of international insurers over the next five years. This may bring innovation and capital, but it also raises important questions about equity, regulation, and affordability.

Ultimately, the choice before India is clear. Healthcare can remain a last-resort safety net, or it can be treated as productive national infrastructure, much like roads, power, or digital connectivity. Infrastructure is necessary and insurance is essential, but priority determines outcomes. Without a decisive increase in public spending, India will continue to achieve impressive results with limited resources—while paying a quiet but persistent economic price.

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

Leave a reply

Leave a reply