Upon return from my Everest Base Camp (EBC) trek, I expected questions about the majesty of the Himalayas, the spiritual silence of the trails, or the indelible sight of the Khumbu Icefall. But the most common question I got was: “After an ischemic heart disease attack, how did you go on to perform such a strenuous trek in subzero conditions? Were you not scared?”

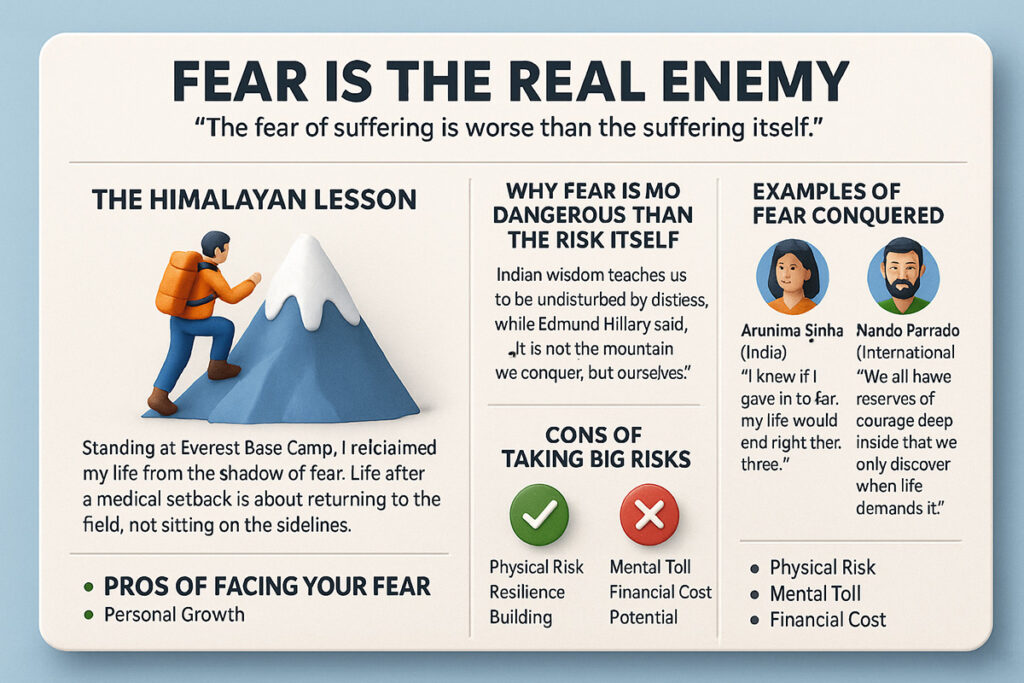

The reality is, I knew the dangers. Yet I wasn’t scared as they conjured up. Just as Paulo Coelho says in The Alchemist: “The fear of suffering is worse than the suffering itself.” Fear, I’ve come to understand, is not the protector we suppose it to be—it is more likely the robber of one’s possibilities.

At 5,364 meters and surrounded by snowy peaks older than time itself, you realize something great: the human heart is constructed to ascend, not only in height but in bravery. When I first took a step towards EBC, I was not challenging my heart condition; I was taking back my life from the darkness of fear. Yes, there were times it got so cold that the cold seared through my gloves, times it felt like I had legs of stone, and times my breath became an expensive commodity in the thin air of mountains. But every step taught me that post-medic setback life is not sitting on the bench—it’s about stepping back into the field, though the rules have been altered.

Fear has a biological function—it is meant to protect. But unchecked, it creates a prison of one’s own accord. Indian teaching puts this reality in a Bhagavad Gita verse: “A person who is not disturbed by happiness and distress and is steady in both is certainly eligible for liberation” (BG 2.15). Fear holds us fast in distress before anything has happened amiss. It freezes action and subjects possible experiences to “what-ifs.” At the global level, mountaineer Edmund Hillary said it in a nutshell: “It is not the mountain we conquer, but ourselves.”

In EBC training, the highest mountain I had to defeat wasn’t in Nepal—it lay in the inner recesses of my mind. The trek itself simply verified the preparation already undertaken on my psyche. Biting back fear in the face has great dividends. All risk we face extends the limits of comfort. I returned from EBC with stronger lungs and legs but also an unconquerable sense of self-assurance. Experience of this nature builds resilience that will weather future storms, be it health issues, business reverses, or relationships. That feeling of satisfaction is entrenched and long-lasting, and your courage may inspire others. One of the other trekkers approached me privately and said one day, “If you’re capable of trying this despite following heart disease, I am capable of tackling my fears as well.” First and foremost, through taking that risk, I averted the constant regret of one day thinking, “What if I’d only tried it?”

That said, it is important not to romanticize risk. Some fears are rooted in reality, and preparation is non-negotiable. Strenuous treks carry physical risks, especially for those with medical histories, and the possibility of altitude sickness or cardiac stress is real. Fear can also take a mental toll, resurfacing during moments of exhaustion or uncertainty. There are financial considerations as well, since adventures like these require investment in training, gear, and travel. And there is always the possibility that pushing too hard, too soon could lead to setbacks.

Courage, therefore, should never be confused with recklessness. Before EBC, I underwent a cardiac stress test, followed a carefully structured training plan approved by my doctor, and built endurance over months. My decision was informed, not impulsive. This balance between courage and caution echoes Chanakya’s wisdom: “Before you start some work, always ask yourself three questions—Why am I doing it? What might the results be? Will I be successful? Only when you think deeply and find satisfactory answers, go ahead.” Fear loses its grip when preparation replaces uncertainty with confidence.

History and the present world hold countless cases of people overcoming fear to reach the heights of achievement. Arunima Sinha, whose leg got amputated in a train accident, became the first amputee female climber of Mount Everest. She has said on occasion, “I knew if I gave in to fear, my life would end right there.” Around the world, Nando Parrado, one of the 1972 Andes plane crash survivors, walked out of the mountains after 72 days in order to rescue his companions. The ordeal taught him that “We all have reserves of courage deep inside that we only discover when life demands it.” These accounts teach us that risk is real, as is the strength we all possess within.

The truth is, you don’t need to travel to Everest Base Camp in order to face fear. It could be standing up in a meeting despite inner fears, making the first move toward a career change, traveling solo into an unfamiliar city, or taking a class that you’re terrified of. With every action you take despite fear, you grow your ability for life.

As the friends questioned me afterward, “Were you not afraid?” I gave them an honest answer: “I was more afraid of not living.” Fear teaches us of risk, but it also lies—it makes you think that the cost of action is higher than the cost of regret. Your real enemy is neither the cold of Himalaya nor thin air nor open heart—it is letting fear write the end of your story. As Paulo Coelho’s Santiago discovered, without risk, there is no reward. Whatever your “Everest” may be—whether it’s a mountain, a personal challenge, a bold career move, or a health journey—remember this: “The fear of suffering is worse than the suffering itself.” Climb it, step by step, breath by breath. And when you reach your summit, you will realize that fear was never the mountain—it was only the mist that tried to hide the view.

Leave a reply

Nice sir ❤️❤️

ReplySo motivating Doctor

ReplyGreat achievement buddy. Congratulations 🎊 👏 💐 🥳

ReplyAwesome 👏👏

ReplyAnd very inspiring Sir

*Dear Dr. Prahlada N.B Sir,*

Your *Everest Base Camp trek* is a testament to your unwavering spirit and determination. Despite facing a heart condition, you pushed beyond the boundaries of fear and doubt, inspiring countless others to do the same. Your journey is a powerful reminder that fear is not a barrier, but a catalyst for growth and transformation.

*A True Inspiration* :

Your story resonates deeply with the wisdom of *Paulo Coelho,* "The fear of suffering is worse than the suffering itself." You embodied this philosophy, confronting your fears head-on and emerging stronger. Your experience at Everest Base Camp is a shining example of human resilience and the power of the human spirit.

*Preparation and Courage* :

Your approach to the trek was meticulous, with careful planning and preparation. You underwent a cardiac stress test, followed a structured training plan, and built endurance over months. This balance between courage and caution is a valuable lesson for all of us, echoing the wisdom of *Chanakya,*"Before you start some work, always ask yourself three questions—Why am I doing it? What might the results be? Will I be successful?"

*A Symbol of Hope* :

Your story has inspired others, including the fellow trekker who approached you, saying, "If you're capable of trying this despite following heart disease, I am capable of tackling my fears as well." You are a beacon of hope, showing us that with determination and preparation, we can overcome our fears and achieve greatness.

*A Message of Empowerment* :

Your journey is a powerful reminder that we all have reserves of courage deep within us. As *Nando Parrado* said, "We all have reserves of courage deep inside that we only discover when life demands it." You discovered your own reserves of courage, and your story will inspire others to do the same.

Thank you for sharing your inspiring story, *Dr. Prahlada N.B Sir.* Your bravery and determination are a testament to the human spirit, and your message will continue to inspire others to push beyond their fears and achieve greatness. ✨ 🤝 🙏

ReplyLiked it, esp the last sentence

Reply