I became a laughingstock on social media when I claimed that there are more than 800 surgeries in the Otorhinolaryngology specialty. Even I was surprised when I stumbled upon this number. A few years back, I joined a corporate hospital as a senior consultant on a fee-for-service basis. Previously, there was no Otorhinolaryngology department there, and I had to establish everything from scratch. One of the first tasks assigned to me by the finance and billing department was to fix the fee for various Otorhinolaryngology surgeries. Unable to source this information from any other hospital in the city, I turned to the surgical logbook I had meticulously maintained. Indeed, I had performed more than 800 types of surgeries up to that point, each mentioned in our various textbooks, at least once, with good results and minimal complications.

Medical science has taken a giant leap in the last few decades. Specialties have given way to subspecialties and super-specialties. The general trend is to practice more and more about less and less! Necessity is the mother of evolution, and surgeons like me, practicing in peripheral areas, cannot restrict ourselves to a narrow area of our specialties. Moreover, in our country, there is no cap on the types of surgeries we can perform within our field under appropriate conditions. Rather, there is a lot of overlap with many other branches of medicine.

The question here is not the number of surgeries in Otorhinolaryngology. Many junior colleagues who participate in our training courses ask me if it is possible to learn so many surgeries. When mastering anything requires a narrow field focus, how can we be proficient in such diverse surgeries of a vast field like Otorhinolaryngology? The answer is, as Rome was not built in a day, we cannot attain skills in a short period, at least not in my time.

Let me illustrate this point with a legend about Pablo Picasso. When in the market, a woman charmed by his work approached him to draw something for her. Picasso obliged, creating a beautiful sketch within a few seconds and handed it to her. Admiring the drawing, the woman was shocked when he said, “That will be thirty thousand dollars.” She protested, “But Mr. Picasso, how can you charge so much for a drawing that took only a few seconds?” Picasso replied, “Madame, it took me thirty years to learn that art.” Italian sculptor Michelangelo said, “If people knew how hard I worked to achieve my mastery, it wouldn’t seem so wonderful at all.”

My journey was not comfortable either. It took me more than 20 years of arduous work to learn the nuances of these surgeries, one at a time. It was a long and protracted journey of hard work and perseverance, akin to the prolonged efforts of the PWD of Rome! I am still learning. Surgical training is comparable to martial arts Karate, which has nine levels of proficiency, represented by different colors. A gakusei, or student, starts with a white belt. He becomes a Deshi, a top student, or a Sensei, a teacher or master, when he attains the black belt after advancing through all levels. It’s important to note that the white belt gakusei receives the same karate training as the black belt gakusei. The only difference is the amount of practice. The black belt gakusei has the same fundamental skills as the white belt gakusei, but with ample practice.

Similarly, the surgical field has many levels of learning across different surgeries. An experienced surgeon is a master, or black belt, of what he has already learned and a white belt of things he has yet to learn. Like success, mastery is a journey. As Gary Keller, author of “The One Thing,” aptly says, “The path is that of an apprentice learning the basics on a never-ending journey of greater experience and expertise.”

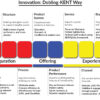

American author Marianne Williamson once said, “The top of one mountain is always the bottom of another.” A mountaineer doesn’t stop after scaling one mountain. He moves on to the next, taller ones, carrying the experience of previous climbs. My surgical goals and journey were akin to that of a mountaineer. During the initial period of my career, I focused on one subspecialty at a time, with deliberate practice, until I reached a reasonable level of mastery. Here is a slide from one of my presentations, which depicts my otological journey, comparable to that of a mountaineer.

Psychologist K. Anders Ericsson published an article in 1993, “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance,” in the journal Psychological Review. This landmark publication challenged the earlier notion that expert performers were gifted, natural talents, or even prodigies. Ericsson proposed the “10,000-hour rule,” providing the first real insights into mastery. His research concluded that elite performers are the result of a typical pattern of regular and deliberate practice over the years.

Ericsson’s premise was based on his observation of elite violinists who had accumulated more than 10,000 hours of practice by age 20. Malcolm Gladwell’s best-selling book, “Outliers,” is primarily based on Ericsson’s findings. “Time on task, over time, eventually beats talent every time,” says Gary Keller. He suggests that most elite performers achieve this feat in about ten years, assuming they practice deliberately for three hours a day, every day of the year. If we allow ourselves some resting or family time and work only five or six days a week, it takes more time.

With deliberate practice, American pilots trained at the TOP GUN school, made famous by the movie of the same name, improved their performance by 1,150%! Previously, Americans were losing their fighter planes at a 1:1 ratio during the Vietnam War. Through deliberate practice, they managed to reduce this to 12.5:1.

There’s an apocryphal story about Sunil Gavaskar, one of the best cricketers the world has ever seen. His test cricket score equals the height of Mount Everest in feet. Even as a child, he was a cricketing prodigy. His teammates found it so difficult to get him “out” that they devised a different set of rules for him: he was called out even if he hit a four or six! Gavaskar’s achievements were the result of deliberate practice. His record of playing all 60 overs during the first match of the first edition of the one-day World Cup series, scoring 36 runs not-out, will likely remain unbeaten forever.

Many junior colleagues underestimate themselves, thinking that only a few are blessed to become good surgeons. That’s a mistaken assumption. American psychiatrist Jose Silva said, “I believe that each one of us has been given all of the tools, talent, and training that we need to accomplish the mission we were sent here to do.” The only requirement is taking that first step towards our objective.

Now, times have changed, and Ericsson’s 10,000-Hour Rule has been debunked. We now have new tools, talent, training, and techniques to master any surgery in less time. We have curated an online course, “High VOLTage Learning,” to help our junior colleagues become great and versatile surgeons. The course details will be announced soon.

Prof. Dr. Prahlada N. B

11 October 2020

Chitradurga.

Leave a reply