The recent New York Times article by Gina Kolata, titled “A.I. Is Making Doctors Answer a Question: What Are They Really Good For?” is a thoughtful and balanced exploration of one of the most profound questions facing modern medicine. Rather than sensationalizing artificial intelligence as either a miracle or a menace, the piece respectfully examines the psychological, ethical, and systemic implications of A.I. entering clinical care. It deserves appreciation for capturing the nuanced voices of clinicians who stand at the frontline of this transformation.

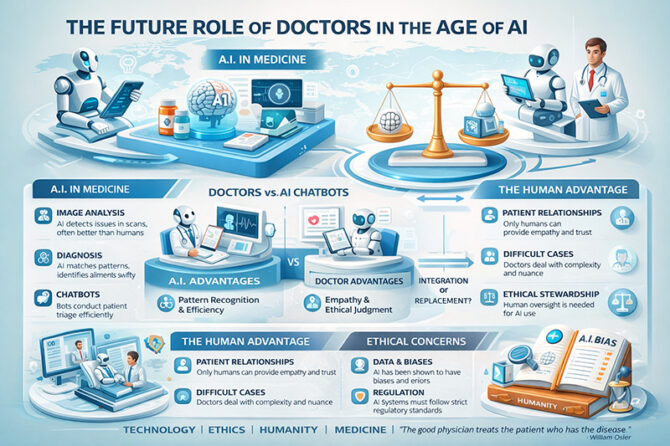

At the heart of the article lies an existential dilemma. Dr. Jonathan Chen of Stanford practices difficult end-of-life conversations with a chatbot before speaking to real patients. He admits discomfort—not because the technology is crude, but because it is so competent. As he reflects, A.I. programs are becoming “existentially threatening,” challenging doctors’ identity and purpose. That candid admission reflects a global unease. When machines can diagnose, interpret scans, draft insurance appeals, and respond to patient portal queries more efficiently than many physicians, what remains uniquely human in medicine?

Dr. Harlan Krumholz of Yale observes that A.I.’s reasoning ability is already outpacing physicians in some diagnostic domains. The article also highlights neurologist Dr. Lee Schwamm’s critical distinction: A.I. excels at pattern recognition but cannot independently extract subtle, context-rich clinical information from patients. Medicine is not merely matching symptoms to databases; it is interpreting ambiguity. When a patient says “my arm was dead,” does that mean numbness or weakness? That subtlety emerges from experience, empathy, and clinical reasoning beyond algorithms.

The international implications are striking. In India, where there is a significant shortage of primary care physicians and specialists, A.I.-enabled triage could dramatically improve access. Consider rural districts in Karnataka or Bihar where a single government doctor may serve tens of thousands. An A.I. triage platform could screen common complaints, flag emergencies such as stroke symptoms, and fast-track critical patients. In urban tertiary centers, imaging A.I. could reduce reporting backlogs in radiology departments, shortening waiting times. This aligns with Dr. Daniel Morgan’s observation that no physician enjoys telling patients they must wait six months for an appointment.

The article provides a concrete American example through Dr. John Erik Pandolfino’s GERDBot, which triages patients with reflux symptoms. By redirecting mild cases to nurse practitioners and reserving specialist time for complex cases, A.I. enhances efficiency. This model could be transformative in India’s corporate hospital chains, where outpatient loads are overwhelming. A gastroenterologist in Mumbai or Delhi could use similar algorithms to prioritize endoscopy slots for high-risk patients, reducing both delay and cost.

However, the piece wisely avoids technological triumphalism. Dr. Leo Anthony Celi of MIT cautions that the danger is not A.I. itself, but deploying it to optimize a “profoundly broken system” rather than reimagining care. This warning resonates globally. In India, if A.I. is used merely to increase billing efficiency or upsell diagnostics, it may deepen inequities rather than solve them. Likewise, concerns about algorithmic bias—where studies show reduced attention to women or individuals with poor grammar—underscore the need for ethical guardrails.

Yet optimism persists. Dr. Adam Rodman argues that while bias exists, A.I. at least allows documentation and potential correction of those biases—something harder to achieve with humans alone. This reflects a broader truth: technology magnifies intent. In well-regulated systems with transparency and accountability, A.I. can become a democratizing force.

From an Indian philosophical lens, one might recall Mahatma Gandhi’s insight: “The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.” A.I. may automate routine documentation and pattern recognition, but service—the human presence at a bedside—remains irreplaceable. Internationally, Dr. William Osler’s enduring wisdom still applies: “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.” No chatbot can replicate lived relational continuity.

The article concludes with a simple but powerful affirmation from Dr. Joshua Steinberg: “Even if an A.I. has read all the medical literature, I will still be the expert on my patients”. That statement reframes the debate. A.I. may master information, but physicians master relationships.

As medicine evolves, the physician’s role may shift from primary diagnostician to interpreter, counselor, systems navigator, and ethical steward. The “scutwork” of documentation and checklist screening, as described by Dr. Robert Califf, can be offloaded. What remains is meaning-making in moments of vulnerability.

The New York Times deserves commendation for elevating this conversation beyond fear or hype. Gina Kolata’s reporting captures diverse expert voices, presenting a global challenge with intellectual honesty and human sensitivity. Rather than asking whether A.I. will replace doctors, the article asks a deeper question: What is medicine for?

The answer may not be technological at all. Medicine, at its core, is a covenant of trust. A.I. may analyze, predict, and optimize—but only humans can sit on a rolling stool, look a patient in the eye, and say, “I am here.”

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

My Values: Creating value for others.

Leave a reply

Leave a reply