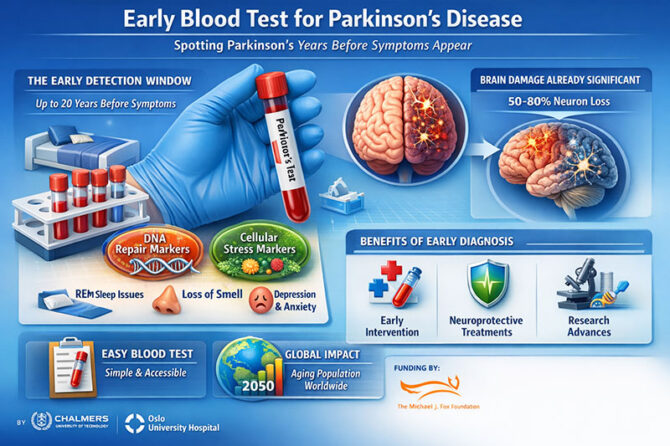

Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology and Oslo University Hospital have reported that a simple blood test could possibly find Parkinson’s disease years—maybe even decades—before the first tremor appears. This could change the future of neurodegenerative medicine. The study, which was published in npj Parkinson’s Disease, gives promise for a disease that already affects more than 10 million people around the world and is expected to more than double by 2050.

The researchers, Danish Anwer and Annikka Polster, should be commended for tackling one of neurology’s most vexing issues: by the time Parkinson’s disease is clinically apparent, 50–80% of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra have already been destroyed. As Anwer points out, finding out about a problem early on could allow for treatment before permanent harm happens. This is an idea that has been tried many times but has not been successful in neurodegenerative conditions.

The Quiet 20-Year Period

Tremor is not the first sign of Parkinson’s disease. Patients may have REM sleep behavior disorder, anosmia, constipation, sadness, or anxiety long before their motor skills slow down and their muscles stiffen. These so-called “prodromal” traits can last for as long as twenty years. However, until today, there has been no proven screening tool that can find disease biology in this early stage.

The Scandinavian research team concentrated on two essential biological pathways: DNA damage repair and the cellular stress response. Cells are always fixing genetic damage and changing how they use energy when they are under stress. In the initial phases of Parkinson’s disease, minor dysregulation in these systems seems to create a temporary biochemical “fingerprint” in the bloodstream. By using machine learning to look at gene expression patterns, the team found a unique signature that was only present in people in the prodromal stage, not in healthy people or people who already had motor symptoms.

This temporal specificity is remarkable. It indicates not merely a biomarker, but a specific biological window—a period during which the disease is active, identifiable, and potentially alterable.

Why Blood-Based Screening Is Important

Researchers around the world have looked into cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, PET scans of dopaminergic circuits, and tests for alpha-synuclein. But these technologies are too expensive, intrusive, or not good for screening big groups of people. A blood test, on the other hand, is easy to get and may be used in large numbers, which is especially important for countries with large populations like India.

In India, where neurological services are not fairly spread out and many patients come in late, early identification could make a big difference. India’s population is becoming older quickly, and at the same time, non-communicable neurological illnesses are becoming more common. The Global Burden of Disease studies have demonstrated time and time again that neurodegenerative illnesses are becoming a big cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) around the world (GBD 2019 Neurology Collaborators, Lancet Neurology, 2021). A straightforward screening instrument included with annual geriatric assessments could significantly alter diagnostic timeframes.

The same thing is happening around the world. The Michael J. Fox Foundation has long been in favour of biomarker-driven research and has given money to projects that look for alpha-synuclein aggregation in peripheral tissues. The current study introduces an additional dimension by concentrating on upstream cellular repair pathways rather than protein aggregation. This more general systems-biology approach might work well with current biomarker techniques.

Consequences for Therapy and Drug Reutilization

The most thrilling implication may reside not solely in diagnosis, but in therapeutic applications. If Parkinson’s disease can be identified prior to significant neuronal death, neuroprotective therapies become feasible. Repurposing drugs—using drugs that were made for different diseases that affect DNA repair or stress response pathways—could speed up the process of turning drugs into treatments.

This change in thinking is similar to what we’ve learned from cancer and heart disease. Mammography screening for breast cancer in its early stages greatly lowered the death rate. Lipid screening likewise revolutionized cardiovascular prevention. Neurology has fallen behind in finding problems before they show up. Parkinson’s disease may be the first major neurodegenerative disease to reach that point.

Annikka Polster said, “If we can study the mechanisms as they happen, it could provide keys to understanding how they can be stopped.” This is a bigger idea: diseases should be halted, not only controlled.

Be careful and think about the situation.

Although promising, numerous concerns necessitate meticulous examination. First, it is important to do longitudinal validation across a wide range of ethnic groups, including South Asian groups. Genetic backgrounds, environmental exposures, and comorbidities vary worldwide. A biomarker profile discovered in Scandinavian populations necessitates validation in Indian, African, and East Asian cohorts prior to extensive application.

Second, there are moral concerns that come up. How ought professionals to advise asymptomatic persons who receive a positive test result? What psychological effects could this knowledge have, particularly in the absence of conclusive disease-modifying therapies? There have been similar arguments over predictive testing for Alzheimer’s disease.

Third, healthcare systems need to be ready. Screening without clear treatment paths risks increasing diagnostic anxiety. So, validating biomarkers and coming up with new treatments must happen at the same time.

A Global Collaborative Achievement

The Swedish Research Council, the Research Council of Norway, NAISS supercomputing infrastructure, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation are all great examples of organizations that support translational neuroscience. Their collaborative model highlights the convergence of academic engineering, computer science, and clinical medicine.

From an Indian point of view, this study should make people want to put more money into biomarker research and AI-driven diagnoses. India’s strengths in biotechnology, computer science, and massive population datasets make it a good place for comparable breakthroughs to happen.

Parkinson’s disease is no longer a rare neurological ailment; it is now a public health priority as people throughout the world get older. The idea that a simple blood test may find disease decades before motor impairment is both scientifically beautiful and socially life-changing.

If this novel idea is proven to work, it might signal the start of a new era in neurology. In this new era, tremors would be stopped instead of just treated, deterioration would be expected instead of tolerated, and a small vial of blood could be the key to keeping dignity in old age.

Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology and Oslo University Hospital have shown a way forward that gives hope. Now, the world’s healthcare systems need to figure out how quickly and ethically to walk it.

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

My Values: Creating value for others.

Leave a reply

Leave a reply