The recent changes in India’s evolving GST 2.0 system can potentially significantly reduce expenses in the Indian healthcare system. The government reduced the Goods and Service Tax (GST) on most healthcare-related goods and services, from basic medicines and diagnostic equipment. Kolkata hospital officials have welcomed the development, terming it as a move that could make it cheaper and easier for patients to be treated. This comes at a time in a country where out-of-pocket spending remains one of the most important contributors to financial distress in healthcare.

The amended form slashes GST from 12% to 5% on a range of life-saving and chronic disease medication. Some medications, such as Agalsidase beta and Imiglucerase, have been exempted altogether. This would entail patients under continuing therapy in cancer and other long-term illnesses enjoying significant relief. Additionally, lifeline medication items and diagnostic materials, such as surgery, radiology, and radiotherapy equipment consumables, now fall into 5% GST only. Health and life insurance cover products have also been exempted, and that could be effective in bringing down premiums as well as expand coverage. These reforms, in general, touch on areas where healthcare spending is most prevalent and yet least accessible.

Hospitals estimate that drugs account for 15–22% of hospital invoices. When the GST on medicines is reduced, patients now enjoy actual cost reductions on overall costs of treatment. Professionals believe that certain oncology patients, in particular, can look forward to 15–20% reductions on costs associated with treatment based on certain specific drugs, and overall costs in hospitals could be cut by 5–7%. Some hospitals have been more precise, predicting an 8–10% cut in overall costs in hospitals. Professionals such as Supriyo Chakrabarty, director of BP Poddar Hospital, and Sajal Dutta, general manager, Desun Hospital, believe that the revisions will afford a significant financial reprieve to families and make superior care accessible by a larger public.

The most immediate benefit of the reforms is price affordability. Direct GST reductions mean fewer out-of-pocket payments by patients on essential medicines and hospital consumables. In a healthcare system in which price all too often dictates access, this could democratize access to care between both rural and urban populations. Insurance waivers could make insurance plans more accessible, potentially increasing the safety net among more households and decreasing the likelihood of negative health spending. Also noteworthy is the benefit accruing to preventive and diagnostic care. With lower-price diagnostics, patients are more likely to make use of early screening, in line with the eventual aim of reducing the burden from end-stage disease on the healthcare system.

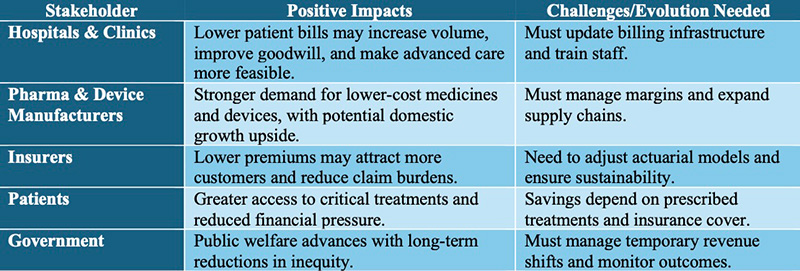

The reforms are set on track to provide a fillip to the domestic healthcare industry as well. Lower costs of equipment and devices and supply materials would stimulate local manufacturing and procurement. Hospitals are set to get greater volumes as cheap care gains traction, and pharma and device companies could get greater orders. The effect could spill into insurance markets as well, with lower premiums leading to greater enrollment and a larger covered pool. All told, the reforms could establish a virtuous cycle of affordability, access, and growth.

Savings, however, won’t be universal. All patients won’t reap broad-based savings. How much patients end up saving will depend a great deal on the medicines prescribed and their expenses. Patients whose treatment plans are less expensive might end up considering it minor. Even in patients with high drug profiles, there are doctor fees, room rentals, and sundry services bundled in the hospital bill and exempted from reforms. The overall saving, therefore, could work out in most patients’ case averages at a mere 5–7%, which, though a help, won’t appreciably make a difference in their billing.

The execution also has its own set of challenges. Medical billing systems are complex, and they involve multiple layers of charge, taxes, and insurance reimbursement. Hospitals and clinics may need to modify billing infrastructure as well as train staff in how to implement the new GST rates and exemption accurately. Inaccurate implementation could cause confusion or, in the worst instance, conflicts with patients and insurance companies. Also, since the government has made a sacrifice in revenue by reducing GST rates in healthcare, it shall require compensatory mechanisms in which public health budgets shall not be impacted negatively.

The business outlook for different stakeholders under GST 2.0 can be summarized as follows:

Another important limitation is that the reforms don’t directly do anything with the price of services such as consultation fees or hospital stay fees. These are typically significant contributors to overall bills, particularly in private hospitals. Until there are reforms in the composition of the fee structure, fiscal relief through GST cuts, though significant, cannot fully solve the problem of affordability.

Ultimately, GST 2.0 in healthcare is a promising policy move in the direction of relief exactly where it is most needed—life-saving medicines, diagnostic equipment, and insurance. The potential savings in the range of 5% and 20% on treatments have the ability to redefine the economics of care both by patients and providers. But it shall be necessary on the part of reforms, in order that they give the maximum effect, that there is fair sharing of advantages, efficient implementation all along the healthcare system, and strict monitoring of results in the real world. These reforms, if implemented well, are capable of unlocking growth in the healthcare sector, relieving financial pressure in households, and enhancing access to potentially life-saving treatments. But reforms cannot be considered in isolation as part of a bigger process in producing healthcare which is affordable, sustainable, and accessible to all Indians.

Dr. Prahlada N.B

MBBS (JJMMC), MS (PGIMER, Chandigarh).

MBA in Healthcare & Hospital Management (BITS, Pilani),

Postgraduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation (MIT, USA)

Executive Programme in Strategic Management (IIM, Lucknow)

Senior Management Programme in Healthcare Management (IIM, Kozhikode)

Advanced Certificate in AI for Digital Health and Imaging Program (IISc, Bengaluru).

Senior Professor and former Head,

Department of ENT-Head & Neck Surgery, Skull Base Surgery, Cochlear Implant Surgery.

Basaveshwara Medical College & Hospital, Chitradurga, Karnataka, India.

My Vision: I don’t want to be a genius. I want to be a person with a bundle of experience.

My Mission: Help others achieve their life’s objectives in my presence or absence!

My Values: Creating value for others.

References:

Leave a reply

Dear Dr. Prahlada N. B Sir,

Your insights on GST 2.0 reforms and their impact on healthcare costs are truly enlightening. By slashing GST rates on life-saving medications and diagnostic equipment to 5% or nil, the government has taken a significant step towards making healthcare more affordable. The exemption of 33 lifesaving drugs, including Agalsidase beta and Imiglucerase, from GST will bring substantial relief to patients with chronic illnesses.

The potential savings of 5-20% on treatments will have a ripple effect, benefiting not just patients but also the broader healthcare system. By democratizing access to care, these reforms can bridge the gap between rural and urban populations, aligning with your values of creating value for others.

However, the success of these reforms hinges on accurate and efficient implementation. Hospitals and clinics will need to adapt their billing systems and train staff to navigate the new GST rates.

Thank you for sharing your expertise on this critical topic. Your commitment to making healthcare more accessible and affordable is inspiring.

ReplyVery insightful!

ReplyThe GST 2.0 reforms are a welcome step that will ease the financial burden on patients and make quality healthcare more accessible